|

|

|

See another section in Articles & Speeches |

|

|

Special

by Elizabeth Lesser

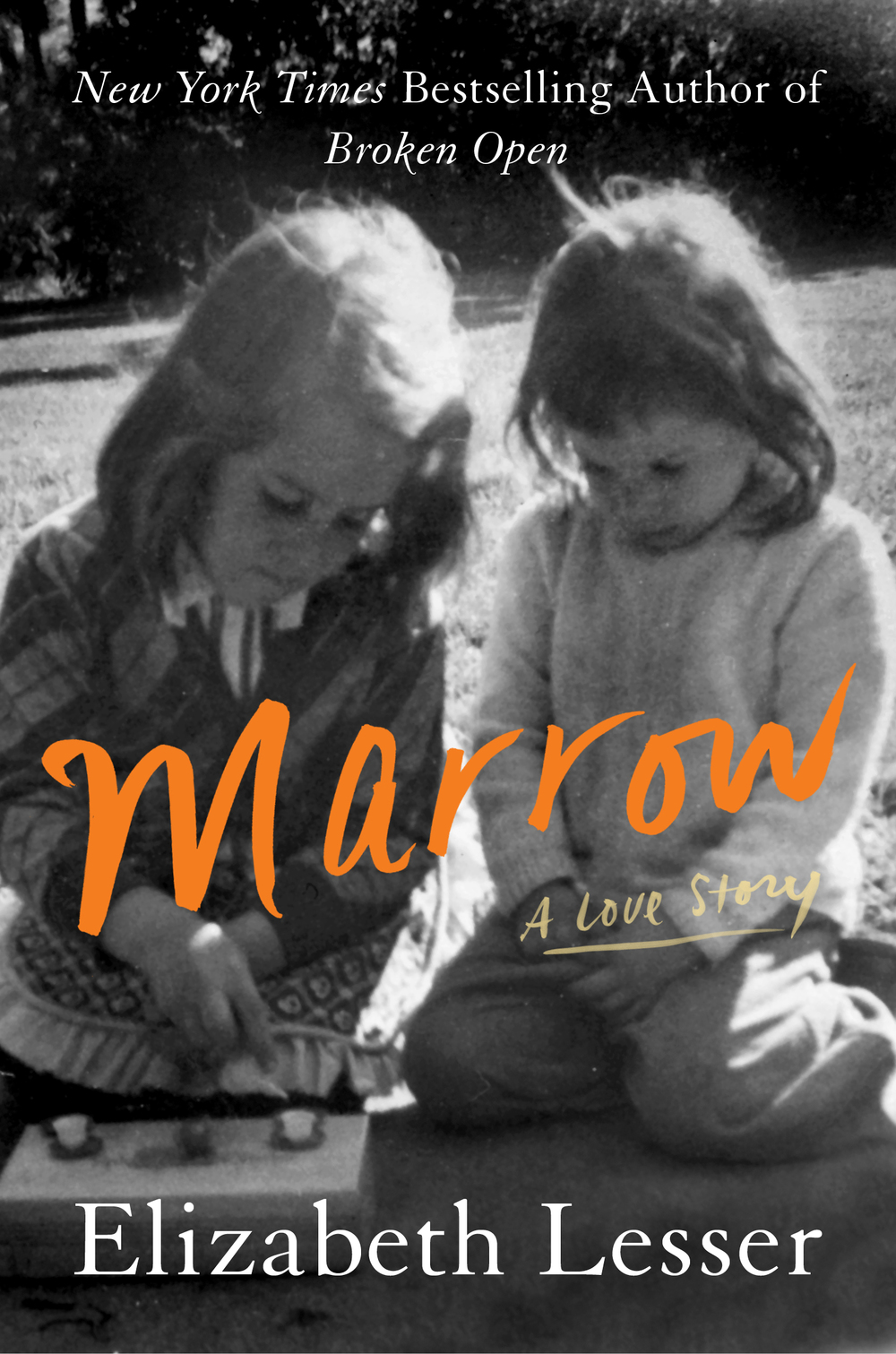

Excerpted with permission from Marrow: A Love Story by Elizabeth Lesser. (Harper Wave, a Division of Harper Collins; September 2016)

I HAVE NOT USED THE word “ego” much in this book. I have left it out deliberately because that one little word—“ego”—contains a complex concept that is often misunderstood and misused in popular culture. And to confuse matters more, different traditions use the same word to describe different ideas. In certain psychological schools of thought, there’s a healthy ego and an unhealthy ego. The healthy ego gives one a strong, authentic selfhood that can play well with others, while the unhealthy ego is wounded and weak. It’s the part of you that views life through an obsessively competitive, comparative lens. Some spiritual traditions describe ego as the mistaken notion of a separate self. The true self feels connected, while the ego feels threatened.

Here’s how I tried to explain the ego to my four-year-old grandson, Will. Two of my grandchildren live in my town. Their parents live here too—but it’s those grandchildren I’m after. On Thursdays I pick Will up at preschool. When I go into Will’s classroom, I feel more privileged than if I were walking the red carpet. To be part of his childhood is a rare gift in this fractured age of family diaspora. I don’t take being a hands-on grandparent for granted. Holding those little animal bodies close to mine is a form of medicine for me. And because I’m a professional voyeur of human development, daily exposure to grandchildren makes me as lucky as the astronomer with top secret clearance at the Hubble Space Telescope. Grandchildren are the ultimate laboratories for witnessing little human beings navigate the art of becoming themselves. Parents don’t get to watch that. They’re too close, too invested, too exhausted.

Thursdays are my Sundays in the church of grandparenting. I get to be with Will all afternoon, beginning with the car ride home. If you’ve raised kids and you also drive, you know that your car is the best place to find out what is going on in a child’s mind. There’s something about the intimate yet private quarters of an automobile—you in the front seat driving, the kid behind you, staring at the back of your head—that makes children open up and say something other than “nothing” when asked that most offensive question, “What happened in school today?”

Today, as I drive Will home, I am listening to a radio interview about the ego, between Oprah Winfrey and the spiritual author Eckhart Tolle. Tolle is a soft-spoken, elf-like man from Germany whose books have sold millions of copies around the world. I have the volume turned down low, just in case Will decides to actually talk to me. Like most little kids, Will has a remarkable ability to practice selective hearing. Whether it’s a radio talk show in a car or a conversation around the dinner table, one never knows if he’s paying rapt attention or completely ignoring the grown-up world. One would assume that a preschooler would tune out Eckhart Tolle, what with his hypnotic voice, German accent, and esoteric subject matter.

So there we are, me driving, pondering Tolle’s words about the ego, with Will in the back, slouched in his car seat. I look in the rearview mirror. Will is gazing out the window, his eyes on the treetops. I turn my attention back to Oprah, who is asking Tolle about the patterns of the unhealthy ego—patterns that keep us isolated from each other, or in conflict, or unable to be in loving, constructive relationships:

TOLLE: Every ego wants to be special. If it can’t be special by being superior to others, it’s also quite happy with being

especially miserable. Someone will say, “I have a headache,” and another says, “I’ve had a headache for weeks.” People actually compete to see who is more miserable! The ego doing that is just as big as the one that thinks it’s superior to someone else. If you see in yourself that unconscious need to be special, then you are already free, because when you recognize all the patterns of the ego—

OPRAH: What are the other patterns?

TOLLE: The ego wants to be right all the time. And it loves conflict with others. It needs enemies because it defines itself through emphasizing others as different. Nations do it, religions do it, people do it.

Suddenly I hear Will talking to me from the backseat. “Granda?” That’s Will’s name for me.

I turn off the radio. “Yes?”

“But Granda,” he says with grave concern, “I want to be special.”

I try not to laugh. I know this is the age a child builds his healthy ego—his sense of being an autonomous and valid person. I know that Will is only four. But it sounds so funny coming from a child, this obvious ploy of the emerging ego. I try to explain what Eckhart Tolle means anyway.

“Well, Will, you are special. But so are all the other kids. You see—”

“No, Granda,” Will says, with great authority. “Only one person can be special. That’s what ‘special’ means.”

I laugh out loud. “You’re right. It does mean that. But everyone wants to be special. So either everyone is special, or no one is.”

In true four-year-old fashion, Will pretends he hasn’t heard me. That’s OK. Like all human beings, if we are lucky, we spend our formative years building up a healthy ego that can go forth into the world, establish boundaries, and express the soul’s purpose. And if we are even luckier, we spend the rest of our life learning how to tame that ego when it gets puffed up or deflated. If we want to know love and experience community, if we want to be part of creating a more peaceful world, we will work to understand this: Either everyone is special, or no one is. Putting yourself or another human being on a pedestal—making yourself or someone else right all the time—is a sure recipe for disappointment or conflict or loneliness.

As I unstrap Will from his car seat and help him out of the car, Will says to me, “And also, Granda, I want to be right ALL the time.”

I think of asking him this question: “So, Will, do you want to be right or do you want to be happy?” But I decide not to. He’ll have to learn this himself. He’ll have to go on the same damn journey we all do—first the strengthening and then the softening of the ego. For now, at four, he’s taking his first steps: being special and being right. An appropriate phase for a kid. But if you are older than four and are struggling with the people in your life, you may want to consider moving beyond those steps. Spiritual maturity is the territory beyond being special and being right. It’s also the territory beyond thinking other people are inherently better than you. Both are afflictions—symptoms on either side of the authenticity deficit disorder spectrum.

I actually remember when I first met my own ego. It is a vivid, visceral memory. I must have been six or seven. I was with my family—my mother and father and my three sisters. We had left our car in a parking lot by the beach, and were heading out to spend a day at the ocean. I ran ahead of the family down a path lined with dune grass and sea roses, feeling a rush of independence, as if the need to be me, and not part of a group, had dropped suddenly from the sky and lodged in my psyche. When I was far enough away from the others, I stopped and dug my toes into the soft sand. I felt the sun on my body and heard the muffled sound of the waves crashing on the shore. I was alone in the dunes. I was me—just me. It was a big, new feeling, one that needed to be marked. I picked a sea rose and put it behind my ear. Then I turned toward my advancing family. I wanted to say, “See me? See how unique I am? How special?” But I didn’t say it, because along with the rush of exhilaration at my sovereignty came an equally strong feeling of shame and self-consciousness, as if a reproaching inner judge had also dropped from the sky.

And so, there it was—my new friend, my ego—in all of its authentic finery and all of its delusions of grandeur and all of its lonely confusion. Thus began a lifelong spiritual journey—the journey toward knowing and loving my uniqueness, even as I understand my unity with all, my nothing-specialness because we all are special. Both are true, and until we make peace with our uniqueness AND our oneness, life here on earth is hard. Here’s the truth: It’s not either/or. It’s both...and more. Ego is not the enemy. But it’s not the whole story either.

We come into the world a potent little acorn, a distillation of the oak we were put here to become. The ego fears it is less than others, or it strives to be better than everyone else. But the acorn only yearns to be the oak. That’s the better urge; that’s the original urge—to be the oak. To be the oak we do not have to keep others from growing into their full selves. We can stand side by side and still reach for the sun. We all belong here. There is room for all of us.

Humanity sure doesn’t act as if there is room for all of us. How did we get to this place of trying so hard to elbow each other out of town that the end result may be a planet that can’t sustain any of us? And how can we work on making things better? My answer always comes back to the most basic human pairing. You don’t have to join a United Nations peacekeeping unit to make a difference in the world. You can start small—with your husband, your kid, your friend, your sister.

Sigmund Freud famously said in 1929, “The great question that has never been answered and which I have not yet been able to answer, despite my thirty years of research into the feminine soul, is ‘What does a woman want?’ ” Seventy-five years later, another smart dude, the Nobel Prize winner Stephen Hawking, was asked by a science journal what he thinks about most often. “Women,” he answered. “Women are a complete mystery.” This from a man who has unraveled some of the most complex mysteries in cosmology and quantum physics.

I have an easy three-step suggestion for Freud and Hawking:

(1) Ask a woman what she wants. (2) Respect her answer even if it differs from your worldview. (3) Tell her what you want. Then, together, the two of you might be able to meet halfway and get on with whatever it is you are finding so mysteriously out of your reach. This same line of thinking applies to all sorts of distinctions between humans. Instead of bemoaning that you don’t understand how a Republican could think the way he thinks, go have lunch with one and find out. Ditto with your gay cousin. Or born-again friend. Instead of building a case in your head against someone who looks different, talks different, or whose way of life differs from yours, get to know people, find the acorn in the heart of the other, and share stories about becoming the oak.

There will always be distinctions between people; at least I hope there will be. Diversity is a hallmark of our life on earth. Biodiversity (which includes human diversity) is necessary for healthy ecosystems. It’s not the diversity that’s the problem; it’s our own ego’s fear of not being the most special one—the special one in our family, at school, at work. A member of the most special tribe, race, religion, nation, species. The Zen teacher D. T. Suzuki said, “The ego-shell in which we live is the hardest thing to outgrow.” Outgrowing the ego-shell is the ultimate freedom.

There is a land beyond the ego’s striving to be “better than,” or its fears of being “less than.” That land is where we know ourselves to be both sovereign and connected—“part of” as opposed to “better or less than.” When you come home to the truth of who you are in the marrow of your soul, you begin to break the ego-shell.

The above is an excerpt from Marrow: A Love Story by Elizabeth Lesser, published

by Harper Wave, a Division of Harper Collins; September 2016 The above is an excerpt from Marrow: A Love Story by Elizabeth Lesser, published

by Harper Wave, a Division of Harper Collins; September 2016

About the author: Elizabeth Lesser is a bestselling author and the cofounder of Omega Institute, the renowned conference and retreat center located in Rhinebeck, New York. Elizabeth’s first book, The Seeker’s Guide, chronicles her years at Omega and distills lessons learned into a potent guide for growth and healing. Her New York Times bestselling book, Broken Open: How Difficult Times Can Help Us Grow (Random House), has sold more than 300,000 copies and has been translated into 20 languages. Her latest book, Marrow: A Love Story (Harper Collins/September 2016), is a memoir about Elizabeth and her younger sister, Maggie, and the process they went through when Elizabeth was the donor for Maggie’s bone marrow transplant. For more information, visit www.elizabethlesser.org.

More features at Feminist.com from Elizabeth Lesser:

|