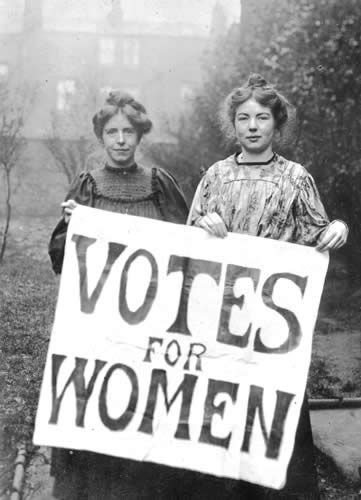

2020 was the 100th anniversary of the ratification of the 19th Amendment, which guaranteed and protected women’s constitutional right to vote.

Women’s suffrage

The fight for this right was initiated by well-known suffragettes, including Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott. In July of 1848, these women, who had already been working as abolitionists, led a convention in Seneca Falls, New York, to discuss their goal of fighting for a better society for women. At the convention, Stanton introduced the “Declaration of Sentiments and Grievances” — a document similar to the Declaration of Independence, but far more specific to and inclusive of women. The assembly ratified the document and passed 12 resolutions, including one that advocated for women’s right to vote.

It wasn’t until June 4, 1919, however, that Congress finally passed the 19th Amendment.

Not all women

Black women worked alongside white women throughout the suffrage movement, which was, in many ways, entwined with the abolitionist movement. Notable leaders such as Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, Maria W. Stewart, and more, were invaluable contributors to the fight, as was Frederick Douglass without who, historians argue, the resolution demanding women’s rights to vote may have failed. Sojourner Truth, a former slave, is still widely known for delivering her “Ain’t I A Woman” speech in 1851 at a national women’s rights convention in Akron, Ohio.

When the 15th Amendment, which was adopted in 1870 and only enfranchised black men, was proposed, however, white suffragettes began to alienate themselves by insisting that white women should be able to vote before black men. Racist remarks, particularly made by Stanton and Anthony, contributed to a faction; they distanced themselves from organizations that promoted universal suffrage and even condoned white supremacist behavior to garner southern support for suffrage.

This treatment continued for decades. In 1913, at a women’s suffrage parade organized by Alice Paul, Ida B. Wells-Barnett was asked to march in the back of the parade. Wells-Barnett was marching as a representative of the Alpha Suffrage Club, the first Black woman suffrage club in Illinois. She refused.

Blocks to voting post-amendment

Even after the 19th Amendment was ratified, black women in the Jim Crow South still encountered disenfranchisement. It wasn’t until the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and subsequent court decisions, that the tools commonly used to disenfranchise black people, like poll taxes and literacy tests were officially outlawed. Of course, the disenfranchisement of black citizens, men and women, still continues today, thanks to racially biased election laws like voter-ID legislation and automatic voter purges; in fact, studies show that voting is routinely harder for people of color than for their white counterparts.

Learn more about the 19th Amendment at the Women’s Vote Centennial Initiative.

|