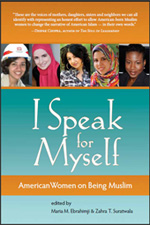

The following is an excerpt from I Speak for Myself: American Women on Being Muslim. Copyright © 2011, Maria M. Ebrahimji and Zahra T. Suratwala. Reprinted with permission from White Cloud Press.

There are pieces of me There are pieces of me

that stand on mountains

that sparkle

in tide pools

that contemplate

in deserts

that glisten

in city lights

but the whole of me

lies everywhere

and nowhere

at once.

If someone were to ask, “Who are you?” I might say I am a Palestinian American Muslim born and raised in Southern California and a descendant of refugees. I might tell them I love hiking, taking walks, learning people’s stories, working with children, listening to music. I might also tell them that even though I can’t draw or sing to save my life, I believe I have the soul of an artist. To describe who I am is to describe all of my fragmented pieces; they belong in several places, yet not wholly anywhere. God says in the Qur’an, “And on Earth there are signs for those with certainty, and in yourselves, will you not see?” (20–21:50).

My journey to find peace and wholeness has been intertwined with my relationship to nature. Although I did not begin to holistically understand my faith until recently, I unwittingly sought the guidance of God throughout my life by connecting with His presence on earth. This connection has helped me put the pieces of my Muslim identity together. My innate inclination to be in nature was, in reality, my subconscious desire to follow the fitra (innate desire) to be near God.

Talk to the Animals

As a child, I was drawn to nature. I believed I could communicate with animals. With a gentle touch of my hand, Lara, our German Shepherd guard dog, would stop barking at whoever was at the door and sit peacefully at my side. With Lara often tagging along, I explored the brush on the hills surrounding my house, finding “rare” insects and shoving them under microscopes. When I felt like losing all of my senses, I would hold my hands tightly across my chest and roll down the grassy hills in our neighborhood park. Dizzy, I would stand up, everything still spinning as I smelled the soil and freshly cut grass and felt the earth’s dampness on my clothes. I would often run down those same hills flying kites. Watching the wind lift my little plastic diamond, I was amazed that something so small and insignificant could look so grand and beautiful.

I felt most at peace while immersed in nature. Consciously, however, my understanding of my faith was muddled. At Sunday school, we learned mainly about what we were and were not allowed to do. I knew that as a Muslim, I was supposed to believe in the Prophet Muhammad (peace and blessings upon him) and I was not allowed to eat pork. I knew we had two major holidays, during which I got money from my parents. I knew that at the mosque I had to cover my hair. We were taught rituals without meaning or context, expected to do things for the sake of not being punished by God. We were not taught about the Prophet—how he had lived his early childhood in the deserts of Mecca and had spent time meditating in nature, where the Qur’an was revealed to him only after countless hours of reflection in the cave. At that age, I did not connect my desire to be near the creations of God to a desire to be near God. All I knew was that in nature I felt peace. In the years to come, I would search for that same feeling within my faith.

Among my peers at school, I was painfully shy and reserved. One of the few brown kids in a mostly white neighborhood, I rarely spoke up in class and tried my best to be invisible. My tan skin and dark features were, in my mind, a deficiency. I often wished I had a “normal” name, yellow streaked hair, and lightly sunburned skin. Despite my efforts to not be noticed, curious and ignorant individuals often called attention to my differences. I was frequently having to explain that yes, my tan was natural and I guess I was lucky to have it all year round, and no, I had never ridden a camel. Frequently they would ask, “Where are you from?”—increasingly making me feel that I did not belong there and that I was an “other.” The only place I truly felt at ease was when I was running around outdoors with Lara next to me, the world spinning around, the smell of wet earth in my nostrils.

Tide Pools and Sunsets

In my early adolescent years, my understanding of Islam remained fractured and incomplete. At that point in my life, my Islam consisted of ritual obligations I did not deeply connect with or understand. Nature was my refuge, my source of peace and balance. I spent my days taking long walks around my neighborhood, my evenings stargazing, and my summers volunteering as a junior naturalist. I took trips to local tide pools, where I poked sea anemones as I felt their sticky tentacles suctioning around my fingers. I hiked the fragrant sage hills, rubbing the leaves between my fingers and piercing cacti with pocketknives to find hidden succulence. I helped clean a local estuary that reeked of sludge and the careless disregard of people. I created works of art out of twigs, leaves, berries, and pinecones, crafting beauty from my surroundings. Those summers, I learned how to use my senses, how to discover the beauty around me, and how to appreciate the splendor in diversity. Years later, I would come to understand this as a form of worship.

In high school, I searched for a tangible relationship with God by establishing regular prayer. Prayer was difficult. I wanted so much to feel connected, but I often struggled to remain in a state of awareness and consciousness of God. My favorite part of prayer was the moment when, upon completion, I would sit on my prayer rug, raising my hands up and just talking to my Creator, asking Him for guidance, mercy, and blessings. There was something powerful about feeling I was conversing with God. It made me think of another time I would feel compelled to make dua, or supplication—while I was in nature. My favorite spot was on a bench near my home that overlooked the tide pools. From my vantage point, the tide pools looked deceivingly small and simplistic: jaggedly curvaceous rocks holding little pools of water. I knew, however, that in reality there was an amazingly complex ecosystem living in the shallow pools of those rocks.

Like the scattered pools, I felt more complex than I thought possible for anyone to understand—fragmented, disconnected, and without a sense of wholeness. I wasn’t sure who I was, but I often asked God to make me into the person I wanted to be: strong, confident, artistic, beautiful, and most importantly, whole. Subconsciously, it was my fitra that drew me towards God as I reflected on His creation. It was at this point in my life that I began to bridge together my ideas of nature and worship.

During my junior year of college, September 11 occurred. Being one of the few Muslims on our campus, I had the opportunity to speak on behalf of my faith. I sat on campus panels educating people about and defending Islam. Over and over again, I found myself lumped into the category of “them.” It became increasingly important to me that I figure out my own individual relationship with Islam. I decided to study the religion more, and in doing so, I began to understand its deeply spiritual elements. Once again, I drew a parallel to the reverence I felt when surrounded by nature. The brilliant smoggy Los Angeles sunsets that streaked the skies with violet, magenta, and mandarin reminded me daily that amidst the murky passages of life’s journey comes the vividness of Majesty.

Mountains

In 2007, I moved to Washington, DC, somewhat unexpectedly. Having just completed my master’s degree in counseling, I was visiting friends and family in the DC area. I ended up canceling my return ticket to California. I had met so many kindred spirits: artists, teachers, environmentalists, lawyers, soul-searchers, philosophers, human rights advocates—all beautiful in their uniqueness. I had never been around such intensely passionate, dedicated, and inspiring individuals. Through a dear friend of mine—one of the founders of DC Green Muslims—I became involved in connecting Islam to environmental issues. We had numerous discussions on the intertwining of God-consciousness with the environment, and we worked in the community doing service projects. My humble participation in this group helped me connect two distinct elements in my life that I had only partially associated in the past. Although I still perceived my identity as fragmented, I started to experience my spirituality as interwoven with my relationship to nature.

It was later that year when I climbed my first physical mountain. Accompanied by my good friends Jasmine and Ibrahim, I steadily made my way up Old Rag Mountain in the Shenandoah Valley, approximately a four-and-a-half–mile hike each way. Ibrahim insisted we keep moving so we could catch the view before the sun began to set. I was huffing and puffing the last two miles as we climbed up boulders, stumbled over thick tree roots, and adjusted to the altitude change. A few times, I wanted to give up. I was tired, cold, and worried about the impending sunset. A few experienced hikers coming down the mountain asked us if we were equipped for the dark and bitter cold nightfall would bring. I started to get nervous, but Ibrahim assured us we would be well on our way before it got too dark.

Once we reached the top, I forgot about how much I had struggled to get to that point. I paused, inhaled, and exhaled. Reflecting amidst the glory of God, I was silenced by the beauty before me, awestruck at the sight of millions of trees. I was most struck by the thought that each of these individual trees had gone through the exact same processes as all of the other trees, their leaves all changing to the same shade of yellow in unison. I saw myself as one of those trees, understanding my lifelong search for spirituality and the numberless hours of reflection serving to prepare me for the different seasons of life. I realized that even though my struggle is unique to my experience, I was part of a forest. I felt connected to the world around me, no longer fragmented. I began to understand myself, my life, and my journey as a means to cultivating my love for As-Salam, An-Nur, Al-Wadud (The Bestower of Peace, The Light, The Loving One).

Rima Z. Kharuf was born and raised in Southern California. She currently teaches special education at a public school and enjoys hiking, learning about social justice issues, and earning frequent flyer miles visiting her family. Rima received her master’s in counseling from California State University, Fullerton, as well as a master’s in education and human development from The George Washington University. She and her husband live in Northern Virginia.

I Speak for Myself: American Women on Being Muslim (edited by Maria M. Ebrahimji and Zahra T. Suratwala, White Cloud Press, May 2011) is a collection of 40 personal essays written by American Muslim women under the age of 40, all of whom were born and raised in the US. It is a showcase of the true diversity found in American Islam. www.ispeakformyself.com

|