|

|

"Sixty"

The following

is an excerpt from the Book: MY

LIFE SO FAR by Jane Fonda. Copyright © 2005 by Jane Fonda.

Published by arrangement with Random House, an imprint of Random

House, Inc. To purchase My

Life So Far, click

here. We are commanded to love our neighbors as ourselves, and I believe that to love ourselves means to extend to those various selves that we have been along the way the same degree of compassion and concern that we would extend to anyone else. If to do so is unseemly, then so much for seemliness. —FREDERICK

BUECHNER, Silence is the first thing within the power of the enslaved to shatter. From that shattering, everything else spills forth. —ROBIN

MORGAN,

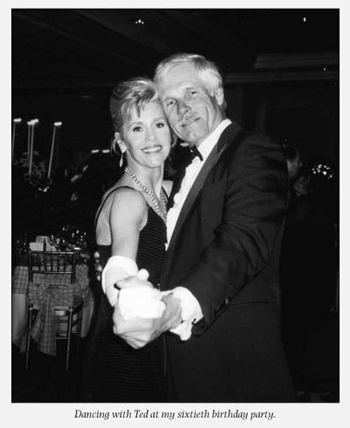

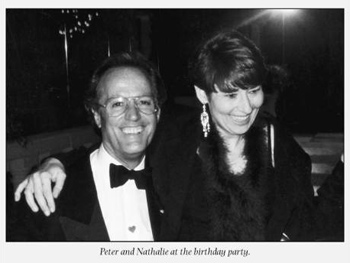

DECEMBER 21, 1997, the curtain went up on my third act. Ted threw me a wonderful sixtieth birthday party. Vanessa designed the invitation: On the front was a yellow road sign reading WORK IN PROGRESS , and it accordioned out into a series of photos of me in various phases of my life, ending with “to be continued.” Our families and friends were there—three hundred in all—and it was probably the most diverse group Atlanta had ever seen. Keeping a secret is near to impossible for Ted, but he managed not to tell me what he was giving me as a gift, only teasing me by saying it was “a gift that would keep on giving.” That night he stood up and told the guests about how I had often said I thought he was smart to have set up his family foundation, because it guaranteed that all his children would be together with him at least four times a year. “So for your sixtieth birthday, Jane, I’m giving you a ten-million-dollar family foundation.” I thought I’d heard wrong. He asked me to come to the stage, and when I stood my knees buckled. I would have gone down had it not been for Max Cleland, one of Georgia’s U.S. senators and a triple Vietnam amputee, who was next to me in his wheelchair. When I got to the stage, I threw my arms around Ted, kissed him, and said to the guests, “He told me he was giving me a gift that would keep on giving . . . but, oh my God! I had no idea.” With the help of my friend the editor Nick Boxer, I had finished the twenty-minute video of my life, and later in the evening I showed it to the guests. Although they seemed interested, even moved by it—especially my women friends—it was of necessity done in such broad strokes that when I look at it today it seems quite superficial. I now realize it couldn’t possibly have had the impact on others that making it had on me, for it changed me in ways that would become apparent only as my third act began to unfold, and in ways I did not necessarily intend.

Toward the end of the video, over images of my life with Ted, I explained in a voice-over how eight years earlier I had decided to leave my life in California and commit to him because I wanted to accept the challenge of intimacy. I talked about how frightening this had been for me; how Katharine Hepburn’s advice to never get soggy had come back to me. And then I said, “Suddenly it hit me: This was what I was supposed to face, my biggest fear—intimacy, the one thing that had eluded me, a true, lasting, intimate relationship with a life partner. If I didn’t make a leap of faith, this would be the thing at the end of my life that was left undone; the big ‘if only.’ ” I was sixty. I had done the hard work needed for intimacy to become a reality, at least on my end. The work was bearing fruit: I was beginning to sense what my marriage could be like if Ted and I really showed up for each other. Working on my birthday video had allowed me to see that there was a “there there” within me after all. It exposed for me the threads of continuity, like suspension bridges, that had spanned the canyons of change in my life. I could see that the main thread was courage in everything except my personal life. As the weeks went by following my birthday, I became aware of feeling more like me, a whole being, standing next to but no longer overlapping into the being that was Ted. I was ready. But I knew it wouldn’t happen unless Ted was willing to make some changes in the way he regarded our relationship. Unfortunately, his tendency was to like things just the way they were, and despite my growing self-esteem I still wasn’t able to come right out and ask for what I wanted—even after I had realized that there could be no truly intimate relationship between us unless I spoke my truth. I still felt I had to please him at the expense of myself. The subtle power of sexist roles and their inherent inequality has been deeply imprinted in all of us raised under them. More and more frequently I’d send him subtle signals about how I was feeling, and when the signals weren’t received, I would drink to numb myself until the anger had passed. If he’d bothered to look closely, Ted could have seen the silent me, like a trout swimming out from behind a rock and coming closer to the surface. But Ted is not a close looker, especially if what he might find would risk muddying his waters, and I—accomplice that I was—wasn’t willing to break the surface. One voice was telling me, Jane, you can’t go on this way, while another (very strong) voice was whispering, Maybe you shouldn’t rock the boat. Things are okay. It’s an interesting life. He’s a wonderful man. Out of love and respect for Ted and his children, I will not go into specifics about what was not working in our relationship. Quite honestly it is not necessary, and I have already given you a sense of the issues. What I can write about (and what is important because of its universality) is how in spite of everything I remained paralyzed when it came to actually speaking up for myself in ways I feared might end the relationship. And I can write about how it took two more years for me to get up the courage to do it. I had been unafraid to travel to North Vietnam in an effort to help end the war; to place myself in harm’s way; to risk public censure; to stand up to the government when I thought what they were doing was wrong. But when it came to a relationship with a man, I still could not raise my voice. And I wasn’t even dependent on him financially! One specific problem that increasingly wore me down was all the traveling. While it had seemed relatively easy and fun at first, I hadn’t realized that it would never end, that we would be continually on the move, like migrating birds, always packing, never totally unpacking. First there was one place in Argentina, and we’d go there for a restful week or ten days of fishing when it was winter in North America. But then Ted added two more properties in Argentina, so that even when we were there we were shuttling from one place to another. Guilt was beginning to set in when I didn’t want to fish every single day, when I didn’t want every hour programmed. Some days I wanted to do nothing ...just read, think. I wanted to acknowledge to Ted that I was on a journey and invite him to join me, but it required slowing down to what psychologist Marion Woodman calls “soulspeed,” and for the driven, soulspeed feels like death. Quincy Jones put it well in his autobiography, Q: I was always running, but every time I ran I kept crashing into myself coming from the opposite direction, and he didn’t know where he was going either. I ran because there was nothing behind me to hold me up. I ran because I thought that was all there was to do. I thought that to stay in one place meant to die. I thought it was a male thing, until I read Miss America by Day, by former Miss America Marilyn Van Derbur, whose father had committed incest with her from age five until eighteen. She writes movingly about how often victims of early abuse (sexual, physical, or psychological) must stay busy, keep moving, so as to avoid feelings that might otherwise arise. Ted had to keep moving so that his demons wouldn’t catch up with him. I felt empathy for him, but I was becoming aware that there was no deepening to our life, just a lateral repetition of scheduled activities. Now that I had started my last act, I wanted to stop all the doing and start being—to slow down and show up. Ted couldn’t. When it came right down to it, I think he was scared. I began to descend into quiet desolation, disappearing into sleep much of the time. Ted, I was discovering, thought that intimacy meant to tell his innermost thoughts to his significant other, which was odd since he told his innermost thoughts to everyone. But listening, in turn, to that other? No. I was becoming aware of how nearly impossible it was to have a two-way conversation with Ted, unless I was talking about something he could easily recognize as relevant to himself. There just wasn’t room in his brain for words other than his own. It’s not as if I hadn’t seen the warning signs. Time was fleeting; color was beginning to drain out of things; the nictitating membrane was settling in; increasingly I found myself engaging in angry mind rehearsals with Ted and venting to my closest women friends. I would think, I don’t want to live laterally anymore, skimming over the surface. Vertical is how I need to live. Moving so fast through life leaves no time for the spirit, for mystery, for the existential. I asked him, “Who are you, Ted? Beneath your worldly successes and the applause and clamor of the crowd, who are you?” I tried to explain by using myself as an example: “I have been an award-winning actor, but that’s just what I did, that’s not who I am. If that was who I am, I’d have been miserable leaving it all behind.” I tried to tell him who I felt I was: a woman in the last act of her life who wanted to be authentic, whole, to deepen my life, to embody the soul I felt hovering around me, asking to be invited in. I love Ted and always will, and I knew that it wasn’t for lack of intelligence that he didn’t understand me. Well, yes, in a way it was—lack of emotional intelligence, the result of his traumatic childhood. Perhaps I could have handled the constant traveling if it hadn’t been for the other things that hurt me; if I had been allowed more time on my own every now and then; if I had been able to spend more time with my emotionally accessible women friends, my children, my organization. Perhaps I would have been able to return to him better able to accept not only his drivenness but his enmeshment. He fears if no one is there to witness him, he will no longer exist. Then something quite unexpected was thrown into this unsettled mix: the magic of grandmotherhood. Vanessa told me she was pregnant, and I knew that I wanted and needed to be there for her in whatever ways I could. Ted had always generously gone out of his way to help Vanessa and me grow closer, inviting her to travel with us, even offering her a job at Avalon Plantation doing what she does so well—organic farming. But when I told him she was going to have a baby and that I wanted to be there for her as much as possible, he exploded in rage. I think he sensed that my energy would be drawn away from him for a while. But frankly I was stunned and disturbed by his reaction. As the time of the birth approached, I told Ted I wanted to be with Vanessa for the ten days surrounding her due date. Although by now he had gotten over his anger, he wasn’t happy about my going. But there was no question that this was where I had to be, and Ted even surprised us by showing up as Vanessa went into labor. It was a home birth at Ted’s farm outside Atlanta, with a midwife in attendance. Theoretically we parents know when our children are grown-ups, yet a part of us is still awed when circumstances force us to see that they’ve grown beyond us. I was impressed by Vanessa’s decision to have a home birth, how she had gone about finding a midwife (home births are not legally sanctioned in Georgia) and prepared herself for all eventualities. I read books she gave me on home birthing, and together we watched videos of actual home births. I realized sadly how I, like many women, had relinquished to doctors my ownership of this ultimate metamorphic experience. This had been true when I gave birth to Vanessa, but now I was watching her do it right—not in the sense that everyone must have a home birth, but “right” in being intentional, fully in charge, informed. In case it might be needed, we preregistered at a hospital and practiced driving there. She carefully prepared a birth plan (instructions the mother gives to the doctors and nurses about what she wants and doesn’t want to happen to her and her newborn). For instance, Vanessa was adamant about having natural childbirth, and she specified that the baby not be taken from her or given any bottles. I stayed with Vanessa and Malcolm for four days after he was born. I was so proud of the brave way she handled the birth and grateful that I could be there to help her with him. I would sit in a rocking chair for hours at a time while she slept, holding Malcolm against my chest, singing the lullabies I had sung to Vanessa thirty years earlier. A May breeze would gently lift the slipcovers on the porch furniture, and as I gazed out over the freshly blooming dogwood, the wild azaleas, and the lake where two swans held court, I felt that life could never get any better. No one had prepared me for the feelings that arose when I held this little boy, Vanessa’s child. I was utterly broken open in ways I had never been before. Malcolm had enabled me to discover the combination to the safe where the soft part of my heart had been shut away for so long. Depths of feeling washed over me, cleansing me, carrying me too far down the new path of intimacy for me to ever want to turn back. Perhaps Ted knew it would be this way and that’s why he had gotten so upset at the news I would be a grandmother. With the birth of Malcolm, the Phoenix that had been on hold for ten years had risen: I also was being born anew. I knew now that I had to muster the courage to ask for what I needed in my relationship with Ted. At the time, these things seemed huge and difficult to me, but looking back, I see that I was asking for reasonable, bread-and-butter, emotional things. I knew that if I didn’t speak up, I would end my life married, yes, but filled with longings and regrets—just what I’d vowed I would not do. Deception is a lousy foundation for intimacy, and sustainability in a relationship is as critical as it is in the environment. Then one day when Ted’s business brought us to Los Angeles, I went to see my therapist. She said, “Jane, the choice is yours. You like challenges, so I am throwing the gauntlet at your feet. Take the challenge. Be brave in your relationship, whatever the outcome will be. Ask him to join you.” I was acutely aware that there was more time behind me than in front of me and that I had to shake myself awake. Maybe Ted would also like to jolt himself onto a new path but didn’t know how. Maybe I’m supposed to do this ...for both of us. I love him enough to try. It was June. We were up early at his ranch in Montana. The sun had barely risen above the Spanish Peaks, yet a sultry air shimmered across the sleeping fields, signaling the hot day ahead. It had taken me two years to muster the courage for this crucial moment. We gathered our fishing gear, and as we were driving over the bumpy dirt road to his favorite part of Cherry Creek, I said, “Ted, I am scared. I feel myself going numb. I need us to try to do some things differently in our marriage, because otherwise I’m not sure I can show up for you the way you want me to.” And I spelled out what I hoped would happen. I don’t remember what he said, only that a rush of discordant, confused emotions suddenly sucked up all the air in the car. He was angry, that much I knew. When we got to the creek he said, “Let’s go fishing and we’ll discuss this later.” As usual we went to separate stretches of water and for several hours I attempted to fish, but my heart was pounding with dread. Oh my God, I thought. What if he actually refuses to try? For almost nine years I’ve made a core part of myself invisible in order to be “good enough,” and now I’ve put it out there. What if ...No, it’s too awful to countenance. For a moment I imagined our marriage going under, like my grasshopper fly disappearing under a riffle. From the moment we got back in the car, I knew things were not going to be as I had hoped. He had not calmed down; anger was boiling. He was fragmented into little pieces, and I could get no traction anywhere to slow him down and explain my feelings in any depth. I should not have been surprised. As is typical of people who don’t speak up, I had overwhelmed him by dumping everything on him all at once—he, who can’t handle change. When we got back to the ranch, all he could do was bang the walls with his fists and his head. I was stunned by his reaction, but I watched him with detachment. I did what I had to do, and for once I am not going to “fix it” by backtracking. That morning I stepped outside the framework that had held me in thrall most of my life and I could not go back. There was detachment but also a sense of free fall, similar to the limbo an actor feels when he or she is morphing into a new character. Only this was my life, and I had no road map.

Over the ensuing months I tried to find ways of making Ted understand my point of view. But it was as though something had snapped, as if he had been hijacked by his emotions and was incapable of hearing me. I was dumbfounded, because I knew he loved me and that our life together was more important to him than the few things I had asked him to try—try! I hadn’t even demanded a “never again.” Yet our life seemed to be crumbling before my eyes. Was it possible that his male identity was so inextricably bound up with things as they were that he would risk losing me to avoid change? There was another factor that, understandably, compounded his fragmentation and convinced him I had lost my mind: He learned that I had become a Christian. Remember Ted’s abhorrence of decisions made without his consultation? Well, this was about as major a one as can be imagined. Several months earlier my friend Nancy McGuirk had taken me to my “next step.” I hadn’t told Ted beforehand, because by then I didn’t feel we were on the same team. Alongside the frantic life we shared, I was living a parallel inner life, where I took care of my own needs. I was used to doing this. I also knew if I had discussed with him my need for spirituality, he would have either asked me to choose between him and it or bullied me out of it. It was too new. I was too raw. Besides, it was not for nothing that he’d been captain of the debating team at Brown University. If I had discussed it with him beforehand, there was no way I could have held up under what I knew would be his blistering attack on Christianity, most of which I actually agreed with. Don’t you know that Christianity, just like Islam, Judaism, and Hinduism, says women are inferior? What do you think the Garden of Eden myth means, anyway? Woman was an afterthought, made from Adam’s rib to serve him, and then was blamed for man’s fall from grace. And what about the witch burnings, the Crusades, and the Inquisition? He had it all at his fingertips. He knew the Bible far better than I did; he’d read it twice, cover to cover, had been “saved” seven times (including once by the Reverend Billy Graham). He had even considered joining the ministry as a young man, in the years before his younger sister died a terrible, prolonged death from lupus and he had turned from God. In hindsight I realize that not telling him was a wildly unfair thing for me to do. But I felt lost and empty. I needed to be filled. An inner life had been emerging for some time, and I needed to name it. I named it “Christian,” because that is my culture. I began to pray every day, out loud, on my knees, and it was like being hooked up to the power of the Mystery that had been leading me for the last decade. It wasn’t so much a learning about the existence of God, because learning implies use of intellect. It was more an experiencing of His presence, a psychic lucidity, that was allowing me access to something beyond consciousness. It wasn’t long, however, before I found myself bumping up against certain literal, patriarchal aspects of Christian orthodoxy that I found difficult to embrace. I will address this in the next chapter. But I discovered that alienation from dogma doesn’t have to mean a loss of faith. Ted’s level of rage and stress in the six months following my speaking up almost incapacitated him. Marilyn Van Derbur gave me an insight when she wrote in Miss America by Day that her early trauma “had literally hard-wired my brain so that my stress level on a scale of one to ten was fifty. If someone humiliated me, I had no way to accommodate the additional stress, so I would go into a kind of craziness.” There had been too much stress, abuse, and instability in Ted’s early life. Anyone who knows him knows that he reacts to stress almost like someone suffering from posttraumatic stress disorder. I had blindsided him with my need to renegotiate our marriage and with my becoming a Christian—and this double whammy acted as a trigger to rage over which he had no control. Ted insisted that it wasn’t normal to change after sixty. I told him I thought it was dangerous not to. While I had become stronger, Ted had not, and my speaking up for myself was a blow from which he could not allow himself to recover. Maybe he was too invested in his projection of me as someone who expressed her needs only if they didn’t threaten his and who would never place another love—for self, for children, grandchildren, friends, or Jesus—above, or even on a par with, her love for him. I had started out hopefully. I knew that other very successful alpha males can, after a certain age, when testosterone levels drop, make the shift, slow down, open their hearts, and reduce the need to perform. I felt that he loved me enough to at least try. In fact, he did say at one point that he would try to do what I had asked in the marriage. For many months I was ecstatic. I no longer wanted to leave myself behind; I wanted sexuality to come out of relationship—eye-to-eye, soul-to-soul pleasure, where everything wasn’t all planned out to a fare-thee-well. He was happy with sexuality that came out of performance. The very thing I had feared the most—that I would gain my voice and lose my man—was actually happening. It wasn’t how I thought the story would end. You see what you need to see in another person, and when your needs change you try to see different things. The problem comes when what you need and what you see isn’t seen or needed by your partner. It doesn’t mean your partner is bad; it just means that she or he wants something else in life. My happiness was short-lived, for I could see Ted withering before my eyes. Clearly he wasn’t going to be able (or willing) to make the journey with me. We agreed to separate. It was only after we separated that I discovered that while Ted was telling me he would try to do things differently he had turned to his old adage: “Hope for the best, but prepare for the worst.” He had spent our last year together looking for my replacement. That was why he seemed to be graying before my eyes: It was killing him to be dishonest with me. The day we parted, three days after the millennium, he flew to Atlanta to drop me off. As I drove from the airport to Vanessa’s home in a rental car, my replacement was waiting in the hangar to board his plane. My seat was still warm. From the Book: MY LIFE SO FAR by Jane Fonda. Copyright © 2005 by Jane Fonda. Published by arrangement with Random House, an imprint of Random House, Inc. To purchase My Life So Far, click here.

|

|||||||

Home | About Us | Features | Ask

Our Team | Inspiration

& Practice | Women of Vision | Resources

Copyright 2010 Feminist.com. All rights reserved.