|

|

On Forgiveness and Faith

These times are so uncertain

Certainly, he is not perfect, nor is he infallible. He does however, exhibit the human capacity to forgive. I was struck too, with the story of a Muslim victim of a post 9-11 hate crime, who is pleading to save the life of the very man that tried to shoot him. The young man, Mr. Bhuiyan said, “[his] parents and his Muslim faith taught him to forgive his attacker.” My parents and family raised me just as Mr. Bhuiyan was raised. I have not faced the terrible loss he did. In nearly two decades of working on violent conflicts, with young people who are victims of violence I learned a few lessons. The Cycle of Violence Over a few weeks of conversation, they came to me after drawing and painting their responses to the question, “What would you do if you had someone act violently against you?” with a new response. “I might just stop and think, maybe that is not the braver thing to do, maybe courage looks different from what I thought it was before.” Another said, “Maybe the courage I need is to break that cycle, be the strong link in the chain. If I respond with violence, the chain keeps on going forward. It’s time to write a new ending to this story.” What’s most powerful is that the lesson was found by their own exploration of the ramifications of violence and a re-scripting of the familiar retaliatory mentality. What forgiveness does to anger Forgiveness is a function of both the mind and the heart. The mind pushes us to seek a balance in the pain we feel, to find the cause and cut it down. When we forgive, we exercise an element of faith. One need not be religious to utilize this type of faith, your commitment could merely be to the belief that humanity deserves recognition. For me, it is my religion that pushes me to forgive, that opens and softens my heart to the possibilities that indeed a position of strength is not to pound back when hurt with the same measure of pain. I work everyday, if not every minute on forgiveness and controlling anger. It takes a form of necessary discipline that I practice sometimes successfully or unsuccessfully. One must be deliberate, daily and determined to forgive the smallest things, then we can be open to forgiving the greater deeds. For my husband and me, we made part of our marriage promises to each other to never yell at each other. It has not been easy, but for us, this fundamental practice has allowed us to feel safe, to know that there is not an explosion waiting for us at the end of an argument. We are still working on it, of course. So I pray nearly every moment to be stronger, to forgive harder, greater, larger, and with more tenacity. I cannot imagine another way for as India Arie says, “how can love survive in such a graceless age?”

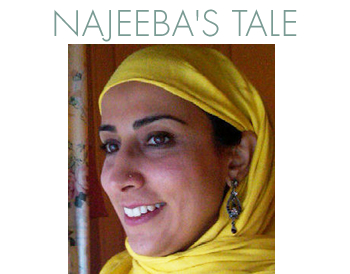

Najeeba Syeed-Miller is a professor of interreligious education at Claremont School of Theology. She is a lifetime peacemaker who has received numerous awards for her work in interracial, gang and interfaith conflicts. The principle by which she lives her life is to save lives. Her conflict resolution experience has made her a sought after trainer for those who work on conflicts in India, Latin America, Guam, and most recently in Israel and Palestine. Her model of intervention is to build the capacity of those closest to the conflict. In particular her research and community activist efforts have focused on the role of women as agents of peacemaking. She is the mother of two children, a boy and a girl and is working on a book about reimagining the role of religion in peacebuilding.

|

||

Home | About Us | Features | Ask

Our Team | Inspiration

& Practice | Women of Vision | Resources

Copyright 2010-11 Feminist.com. All rights reserved.